Economist On Benefits For Mothers Of Having Twins

Throughout history, twins have provoked mixed feelings. Sometimes they were seen as a curse—an unwanted burden on a family’s resources. Sometimes they were viewed as a blessing, or even as a sign of their father’s superior virility. But if Shannen Robson and Ken Smith, of the University of Utah, are right, twins have more to do with their mother’s sturdy constitution than their father’s sexual power.

At first blush, this sounds an odd idea. After all, bearing and raising twins is taxing, both for the mother and for the children. Any gains from having more than one offspring at a time might be expected to be outweighed by costs like higher infant and maternal mortality rates. On this view, twins are probably an accidental by-product of a natural insurance policy against the risk of losing an embryo early in gestation. That would explain why many more twins are conceived than born, and why those born are so rare (though more common these days, with the rise of <a href="https://glowing.com/glow-fertility-program">IVF</a>). They account for between six and 40 live births per 1,000, depending on where the mother lives.

Dr Robson and Dr Smith, however, think that this account has got things the wrong way round. Although all women face a trade-off between the resources their bodies allocate to reproduction and those reserved for the maintenance of health, robust women can afford more of both than frail ones. And what surer way to signal robustness than by bearing more than one child at a time? In other words, the two researchers conjectured, the mothers of twins will not only display greater overall reproductive success, they will also be healthier than those who give birth only to singletons.

Alas, pinning down evolved relationships between fertility and health is tricky. Modern medicine and the pampering effects of economic growth mean that, these days, women everywhere give birth to fewer children than they did in the distant evolutionary past, when human bodies and physiology were forged—even as more of the offspring they do bear survive into adulthood. In Europe and North America this demographic transition began in earnest around 1870.

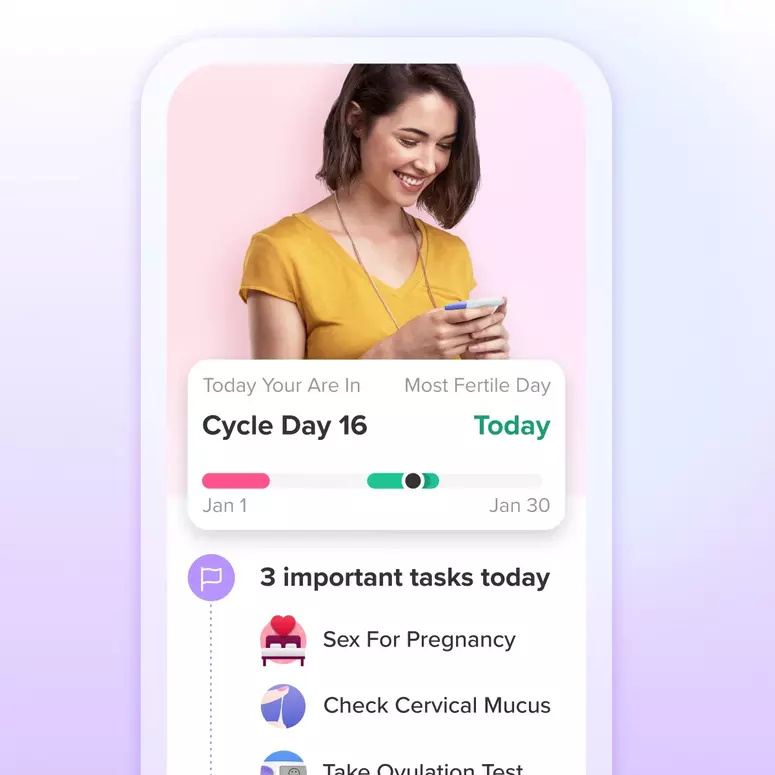

Let's Glow!

Achieve your health goals from period to parenting.