Easter and Christianity

Where Did Easter Come From?

Does the following sound familiar? Spring is in the air! Flowers and bunnies decorate the home. Father helps the children paint beautiful designs on eggs dyed in various colors. These eggs, which will later be hidden and searched for, are placed into lovely, seasonal baskets. The wonderful aroma of the hot-cross buns mother is baking in the oven waft through the house. Forty days of abstaining from special foods will finally end the next day. The whole family picks out their Sunday best to wear to the next morning’s sunrise worship service to celebrate the savior’s resurrection and the renewal of life. Everyone looks forward to a succulent ham with all the trimmings. It will be a thrilling day. After all, it is one of the most important religious holidays of the year.

Easter, right? Wrong! This is a description of an ancient Babylonian family—2,000 years before Christ—honoring the resurrection of their god, Tammuz, who was brought back from the underworld by his mother/wife, Ishtar (after whom the festival was named). As Ishtar was actually pronounced “Easter” in most Semitic dialects, it could be said that the event portrayed here is, in a sense, Easter. Of course, the occasion could easily have been a Phrygian family honoring Attis and Cybele, or perhaps a Phoenician family worshipping Adonis and Astarte. Also fitting the description well would be a heretic Israelite family honoring the Canaanite Baal and Ashtoreth. Or this depiction could just as easily represent any number of other immoral, pagan fertility celebrations of death and resurrection—including the modern Easter celebration as it has come to us through the Anglo-Saxon fertility rites of the goddess Eostre or Ostara. These are all the same festivals, separated only by time and culture.

If Easter is not found in the Bible, then where did it come from? The vast majority of ecclesiastical and secular historians agree that the name Easter and the traditions surrounding it are deeply rooted in pagan religion.

Notice the following powerful quotes that demonstrate more about the true origin of how the modern Easter celebration got its name (emphasis added throughout article): “Since Bede the Venerable…the origin of the term for the feast of Christ’s Resurrection has been popularly considered to be from the Anglo-Saxon Eastre, a goddess of spring…the Old High German plural for dawn, eostarun; whence has come the German Ostern, and our English Easter” (The New Catholic Encyclopedia, 1967).

“The fact that vernal festivals were general among pagan peoples no doubt had much to do with the form assumed by the Eastern festival in the Christian churches. The English term Easter is of pagan origin” (Albert Henry Newman, A Manual of Church History).

“On this greatest of Christian festivals, several survivals occur of ancient heathen ceremonies. To begin with, the name itself is not Christian but pagan. Ostara was the Anglo-Saxon Goddess of Spring” (Ethel L. Urlin, Festival, Holy Days, and Saints Days).

“Easter—the name Easter comes to us from Ostera or Eostre, the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring, for whom a spring festival was held annually, as it is from this pagan festival that some of our Easter customs have come” (Mary Hazeltine, Anniversaries and Holidays: A Calendar of Days and How to Observe Them).

“In Babylonia…the goddess of spring was called Ishtar. She was identified with the planet Venus, which, because…[it] rises before the Sun…or sets after it…appears to love the light [this means Venus loves the sun-god]…In Phoenecia, she became Astarte; in Greece, Eostre [related to the Greek word Eos: “dawn”], and in Germany, Ostara [this comes from the German word Ost: “east,” which is the direction of dawn]” (Englehart, Easter Parade).

As we have seen, many names are interchangeable for the more well-known Easter. Pagans typically used many different names for the same god or goddess. Nimrod, the Bible figure who built the city of Babylon (Gen. 10:8-10), is an example. He was worshipped as Saturn, Vulcan, Kronos, Baal, Tammuz, Molech and others, but he was always the same god—the fire or sun god universally worshipped in nearly every ancient culture. (Read our booklet The True Origin of Christmas to learn more about this holiday and Nimrod’s part in it.)

The goddess Easter was no different. She was one goddess with many names—the goddess of fertility, worshipped in spring when all life was being renewed.

The widely known historian Will Durant, in his famous and respected work Story of Civilization, writes, “Ishtar [Astarte to the Greeks, Ashtoreth to the Jews], interests us not only as analogue of the Egyptian Isis and prototype of the Grecian Aphrodite and the Roman Venus, but as the formal beneficiary of one of the strangest of Babylonian customs…known to us chiefly from a famous page in Herodotus: Every native woman is obliged, once in her life, to sit in the temple of Venus [Easter], and have intercourse with some stranger.” Is it any wonder that the Bible speaks of the religious system that has descended from that ancient city as, “Mystery, babylon the great, the mother of harlots and abominations of the earth” (Rev. 17:5)?

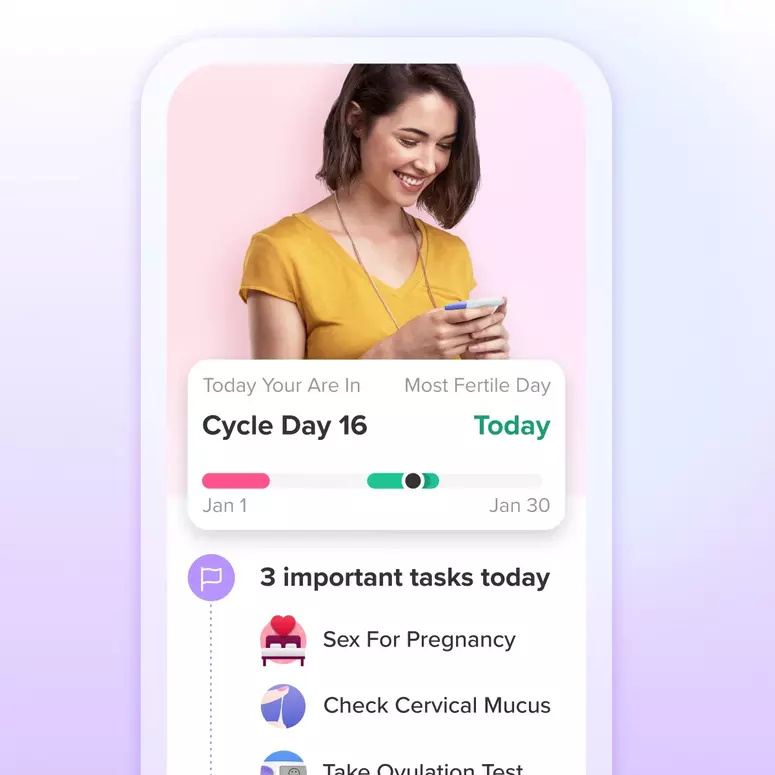

Let's Glow!

Achieve your health goals from period to parenting.