HISTORY LESSON: Did you know about Japanese, Italian and German Americans internment camps?

Two months after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 ordering all Japanese-Americans to evacuate the West Coast. This resulted in the relocation of approximately 120,000 people, many of whom were American citizens, to one of 10 internment camps located across the country. Traditional family structure was upended within the camp, as American-born children were solely allowed to hold positions of authority. Some Japanese-American citizens of were allowed to return to the West Coast beginning in 1945, and the last camp closed in March 1946. In 1988, Congress awarded restitution payments to each survivor of the camps.

The relocation of Japanese-Americans into internment camps during World War II was one of the most flagrant violations of civil liberties in American history. According to the census of 1940, 127,000 persons of Japanese ancestry lived in the United States, the majority on the West Coast. One-third had been born in Japan, and in some states could not own land, be naturalized as citizens, or vote. After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, rumors spread, fueled by race prejudice, of a plot among Japanese-Americans to sabotage the war effort. In early 1942, the Roosevelt administration was pressured to remove persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast by farmers seeking to eliminate Japanese competition, a public fearing sabotage, politicians hoping to gain by standing against an unpopular group, and military authorities.

On February 19, 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which forced all Japanese-Americans, regardless of loyalty or citizenship, to evacuate the West Coast. No comparable order applied to Hawaii, one-third of whose population was Japanese-American, or to Americans of German and Italian ancestry. Ten internment camps were established in California, Idaho, Utah, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, and Arkansas, eventually holding 120,000 persons. Many were forced to sell their property at a severe loss before departure. Social problems beset the internees: older Issei (immigrants) were deprived of their traditional respect when their children, the Nisei (American-born), were alone permitted authority positions within the camps. 5,589 Nisei renounced their American citizenship, although a federal judge later ruled that renunciations made behind barbed wire were void. Some 3,600 Japanese-Americans entered the armed forces from the camps, as did 22,000 others who lived in Hawaii or outside the relocation zone. The famous all-Japanese 442nd Regimental Combat Team won numerous decorations for its deeds in Italy and Germany.

The Supreme Court upheld the legality of the relocation order in Hirabayashi v. United States and Korematsu v. United States. Early in 1945, Japanese-American citizens of undisputed loyalty were allowed to return to the West Coast, but not until March 1946 was the last camp closed. A 1948 law provided for reimbursement for property losses by those interned. In 1988, Congress awarded restitution payments of twenty thousand dollars to each survivor of the camps; it is estimated that about 73,000 persons will eventually receive this compensation for the violation of their liberties.

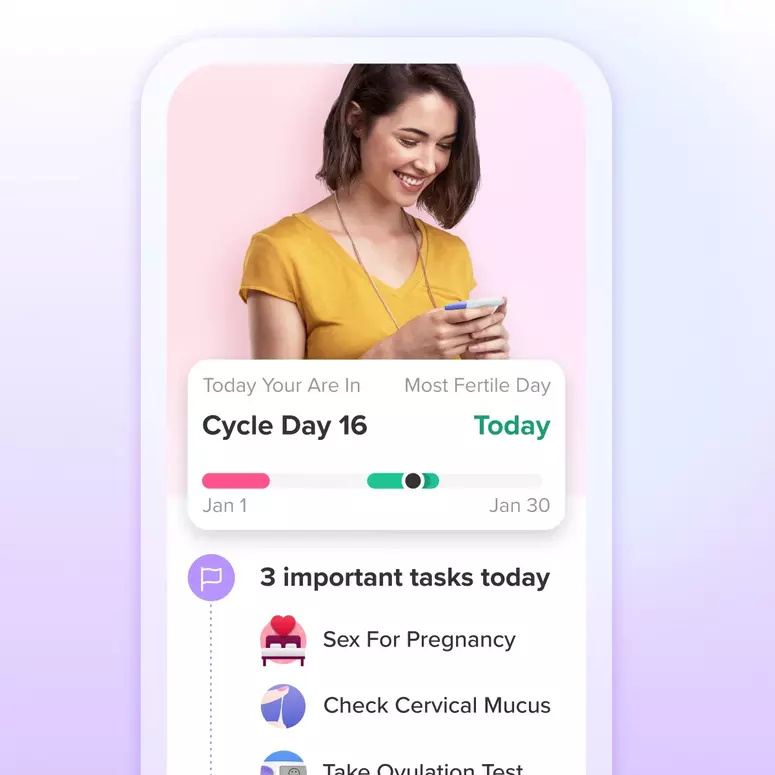

Let's Glow!

Achieve your health goals from period to parenting.