Preventing Miscarriage Caused by Chromosomal Translocations

Another cause of recurrent miscarriage in young women is a different type of chromosomal error called a translocation, which was mentioned in a previous chapter. To understand how translocations cause recurrent miscarriage, let’s use the Encyclopaedia Britannica analogy, borrowed from Dr. Mark Hughes. We have twenty-three pairs of chromosomes. Let’s say that each chromosome is one volume of an encyclopedia. Each volume will contain at least 150 million letters that form words. A gene mutation would represent a misspelling of a single word or, at most, several words. A translocation would represent several hundred misplaced pages of the encyclopedia that are missing from their normal position in one volume, and pasted into another volume. All of the words and all of the paragraphs are intact, but the pages have been mislocated to another volume of the encyclopedia.

Translocations are the cause of many miscarriages. With translocation, part of one chromosome has broken off and moved to another chromosome. In a balanced translocation, using the encyclopedia metaphor, all of the words and paragraphs, and all of the knowledge, is intact, but the order of appearance and organization has been modified. These balanced translocations are found in almost 2 percent of infertile couples (although in only 0.2 percent or less of the general population).

Everything seems to work fine in patients with these translocations, except when they try to have children. For example, if you have a set of encyclopedias in which a single volume is missing 250 pages, and those 250 pages are relocated to a completely different volume, you cannot line up each of those volumes with another set of encyclopedias. If you try to line up the volume that is missing 250 pages with the same volume of a normal set of encyclopedias, it simply cannot match up. Homologous, or “like,” chromosomes must line up during meiosis when either the egg or the sperm reduces its chromosome number from forty-six to twenty-three. For normal reproduction to occur, like chromosomes must be able to find each other so they can prepare for equal separation into the egg and the polar body, or equal separation into two different sperm. This reproductive pairing up, or buddy system, is hampered by the presence of translocations.

Translocations are an integral part of chromosomal evolution and development of species. For example, the genes of most mammals are pretty much the same. We are 98.5 percent mouse and 99.9 percent chimpanzee. In fact, we are approximately 60 percent fruit fly and 40 percent worm. These percentages are calculated by figuring the percentages of strands of DNA in humans that are found identically in other animals. We are all so alike in our DNA that what separates one species from another is that its members are only able to reproduce with other members of the same species. That is the long-range cosmic purpose of chromosomal translocations.

For example, a normal human karyotype when compared to the karyotype of chimpanzees and gorillas contains four major chromosomal translocations. Human chromosome 2 is a Robertsonian translocation of chimpanzee chromosomes 12 and 13. That means that if you took the chimpanzee chromosomes 12 and 13, and stuck them together, you would have what appears to be a human chromosome 2.

In general, most mammals, from rodents to primates, have highly conserved, very similar genes, but these genes are located in different chromosomes and are in a different organizational pattern in the various species, which prevents any possibility of interbreeding. That is the definition of a species. The genes of various species are very similar or nearly identical, but the chromosomal locations for those genes are different. Thus, translocations are an inevitable part of species differentiation, preventing related species from reproducing with each other. But it is also a cause of infertility and miscarriage in human couples.

There are two reproductive problems caused by translocation. The chromosomal confusion, which occurs with large balanced translocations when they try to line up for meiosis, can result in deficient egg maturation or deficient sperm production. However, in cases where sperm production or egg maturation does manage to occur, at least 50 percent of the subsequent fertilized eggs will have what is called an unbalanced translocation.

Remember, balanced translocations are complete reorganizations of where the genes occur on your chromosomes, but they do not affect your health in any way. However, during the shuffling process of meiosis an imbalance can occur with too much or too little of a large chunk of chromosome going to either the egg or the sperm. It is as if a normal volume 13 of a set of encyclopedias has joined up with an abnormal volume 13 that contains 250 pages of volume 14. Remember, either an overdosage of genes or an underdosage of genes leads to severe birth defects or miscarriage. In couples with recurrent miscarriage, a common problem is that either the husband or the wife has this balanced chromosomal rearrangement, i.e., translocation. This leads to an unbalanced chromosomal rearrangement in the sperm or the egg, and subsequently in the offspring. Such a couple may have one miscarriage after another, or, if there is a translocation involving chromosome 21, they may have a Down syndrome child.

However, an alternative is IVF with PGD. A single cell from each embryo on day three can be removed and analyzed for the presence of an unbalanced translocation in the embryo, and only normal embryos would be transferred into the uterus. Some of the embryos from these patients will have balanced translocations identical to their parents’, and some will have completely normal chromosomes with no translocations because they will have inherited only the normal chromosome from each parent. With PGD, the nonviable embryos with unbalanced translocations can be left in the petri dish, and only the normal embryo or embryos with balanced translocations will be transferred back to the woman.

--

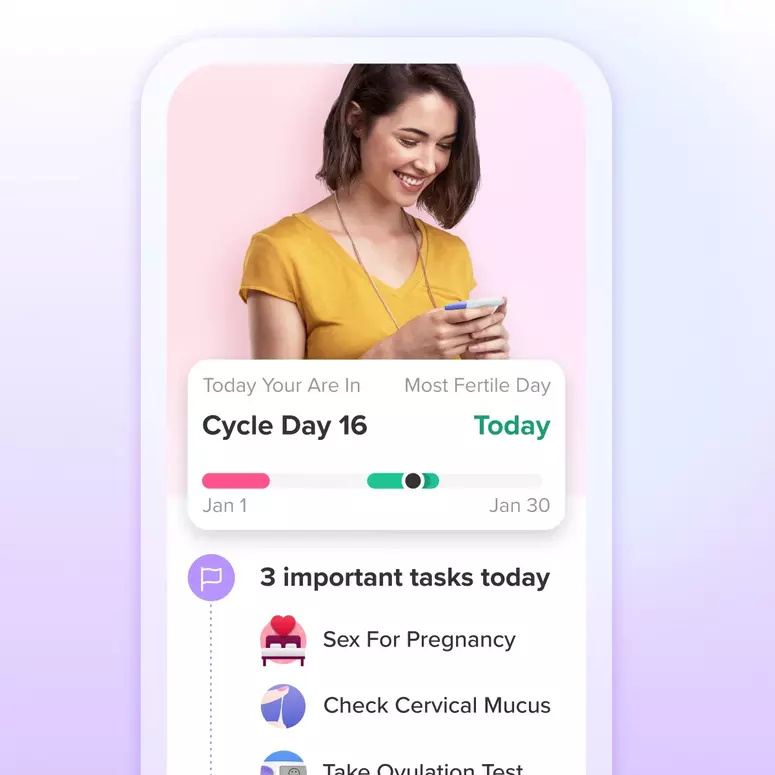

Achieve your health goals from period to parenting.