Death & the Human Body

A more recent news article than the one below sent me down a rabbit hole ( I might post it later as it’s a bit of a different angle) but wondered what other people think about using people’s dead bodies in art?

Would you be interested in participating?

Would/have you seen von Hagens museums?

How would you feel if your relative participated?

I’ll be honest it shocked me at first but I think I can understand why this would be intriguing.

_________________________________________

In every major city in the world there are countless museums that exhibit the products of human culture, sometimes featuring highly unusual themes. However, there is not a single museum about humans themselves—an institution that exhibits the anatomy of healthy and unhealthy human bodies in an aesthetically pleasing way using authentic specimens.

In an interview with National Public Radio’s All Things Considered entitled “Cadaver Exhibits Are Part Science, Part Sideshow,” Body Worlds creator Gunther von Hagens discussed his new millennium plans for a future dead body exhibition. The program’s reporter explained that in 2006 von Hagens sent questionnaires to approximately 6,500 people who wanted to donate their bodies to Body Worlds after they died.

Von Hagens asked some “provocative questions,” according to the radio story: “For example, would they consent to their body parts being mixed with an animal’s, to create a mythological creature? Would they agree to be ‘transformed into an act of love with a woman or a man?’ Von Hagens says that on the sex question, the majority of men liked the idea, while the women did not.”

Von Hagens’s questionnaire should hardly come as a surprise. Since opening in the mid-1990s, the Body Worlds exhibitions have generated equally large ticket sales and audience numbers—44 million visitors and counting as of 2019. What von Hagens has done over the years is produce a portfolio of work that consistently poses dead human bodies in technologically novel ways, even though many of his exhibitions suggest a connection (however tenuous) with centuries-old anatomical displays.

His Body Worlds exhibitions succeed by explicitly using anatomical science’s history and language to produce popular culture narratives about the dead body. His methods always involve plastination, a kind of dead body embalming technology that he defines as “an aesthetically sensitive method of preserving meticulously dissected anatomical specimens and even entire bodies as permanent, life-like materials for anatomical instruction.” Even for the always-industrious von Hagens, however, the exhibition of dead human bodies mixed with animal parts and dead bodies posed in sexual positions sounded far-fetched.

That is, until May 7th, 2009, when Gunther von Hagens opened a new Body Worlds exhibition in Berlin, Germany, called The Cycle of Life (Der Zyklus des Lebens). In one section of the exhibition he and his team posed two different pairs of bodies in sexual positions. Von Hagens released a statement in which he explained that the exhibit “offers a deep understanding of the human body, the biology of reproduction, and the nature of sexuality.” He also made it clear on the Body Worlds website that he wanted to bring the copulating corpses to other cities, such as London.

Each couple consisted of a man and a woman engaged in heterosexual sex. Von Hagens posed the first couple in a sitting position and then sliced their bodies into a thin cross-section that showed the male penetrating the female. The other display involved two, fully formed bodies in which the female corpse was sitting astride the male’s body and the female’s back was to the male’s face. Both couples were in a separate room from the rest of the exhibition, and only viewers ages 16 and up could enter.

During Body Worlds’s over 20 years of existence, it has continually turned the dead body into something new. It is this quest for “newness” (and novelty) that von Hagens is arguably embracing with both The Cycle of Life exhibition and his “provocative questions.” The most productive aspects of those questions have little to do, however, with the controversies that surround von Hagens and Body Worlds. Rather, it is more interesting to ask why positioning the dead body in human sex acts or fusing it with animal parts is itself provocative?

Without too much exaggeration, the bodies in Body Worlds do everything but have sex. Posing dead bodies in sexual positions, perverse as it sounds, is one of the few, common human activities not regularly displayed by von Hagens. Posing dead bodies mixed with animal parts is also not entirely different from the current exhibitions.

One of von Hagens’s more famous plastinates is of a man riding a horse. This exhibit piece is a prime example of the merger between human and animal bodies. Von Hagens has simply proposed to eliminate the demarcation line between rider and horse in order to create a centaur. Displaying dead bodies having sex is certainly more provocative than fusing dead bodies with dead horses, but both these proposals simply encompass the next logical step (and perhaps conclusion) for the Body Worlds exhibitions.

The entirety of Body Worlds is itself a provocation, a dare, a direct challenge to look at the plastinated dead bodies. It is no small coincidence that in America, von Hagens exhibits his work most often with science and natural history museums. By placing plastinated corpses in science museums, von Hagens indulges popular culture’s fascination with the shocking dead body but he also suggests to the viewer that it is perfectly acceptable to look at abject bodies. Add the prospect of dead bodies having sex to the mix, and a science museum’s stamp of approval will only guarantee that the so-called provocation is entirely educational.

In a most peculiar way, Gunther von Hagens has given many museums new financial hope by tapping into an older form of cultural shock, that is, the long-running morbid fascination with the human corpse. To reject von Hagen’s questionnaire out of hand because it seems too perverse, voyeuristic, or gratuitous misses a fascinating series of arguments. Discussing dead bodies posed in sexual positions and the creation of human-animal mythological creatures offers an opportunity to position von Hagens’s overall work among debates in cadaveric anatomy, human taxonomy, and death. It is also far more productive to embrace von Hagens’s provocative questionnaire and its possibilities for the technologies of the corpse.

When The Cycle of Life exhibition opened in 2009, for example, a number of German politicians responded with disgust, shock, and moral outrage. Social Democrats MP Fritz Felgentreu stated, “Love and death are obvious topics for art, but I find it quite disgusting to use them in this way.” Green Party MP Alice Ströver proclaimed, “This couple is simply over the top, and it shouldn’t be shown.” Christian Democratic Union MP Kai Wegner presented a somewhat more pragmatic critique: “I am firmly convinced that [Gunther von Hagens] just breaks taboos again and again in order to make money. It is not about medicine or scientific progress. It is marketing and money-making pure and simple.”

Michael Braun from the conservative Christian Democratic Union stated that the dead bodies posed in sexual positions were “revolting. Hagens rides on a wave of taboo-breaking and the couple plumbs the depths of tastelessness.” To put a dead body on display (even with its anatomy in full view) is one thing. To put a dead body on display with its anatomy sexually positioned in/around/and near another body radically alters that visual tableau. It reduces dead bodies, as von Hagens’s German critics assert, to something vulgar, less human; the corpses become a great deal more animalistic.

Von Hagens is inviting the viewer to look at and take total control of an utterly impossible situation—but a situation his questionnaires suggested men strongly supported and women wanted no part in. Even then, the female body is still subjected to a postmortem objectification and sexualization that parallels the everyday lived experiences of many women.

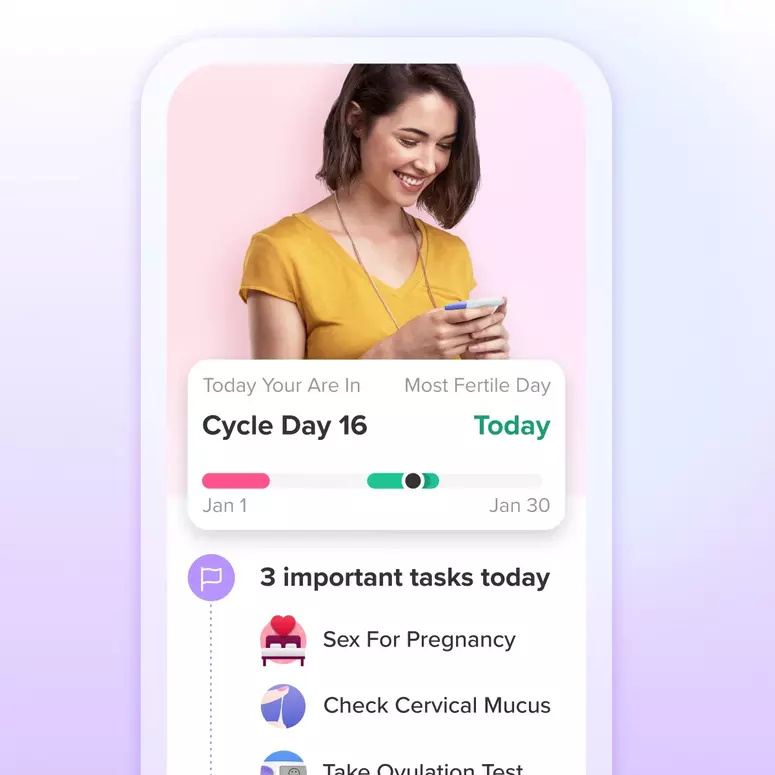

Achieve your health goals from period to parenting.